Glasgow fights same battles decades after Edinburgh’s HIV epidemic

Gilbertson was one of thousands of young people who became hooked as the city flooded with heroin in the late 70s and early 80s. She is telling her story on award-winning director Stephen Bennett’s Choose Life: Edinburgh’s Battle Against Aids. The new documentary is about the HIV epidemic which began to take hold of the capital 40 years ago, and went on to kill Gilbertson’s partner and many others.

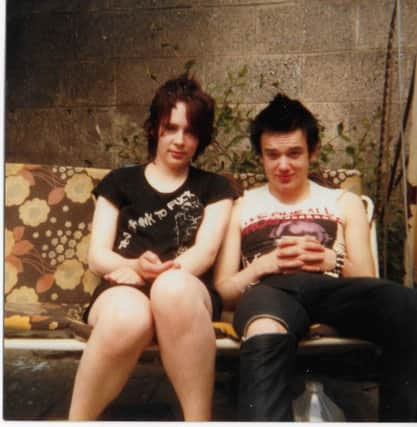

Gilbertson can remember the exact moment she fell in love with Raymond: “a sweet, flamboyant boy” 18 months her junior. “We were outside a pub and we had been dating for a wee while, and there was going to be a huge fight between the punks and the skinheads,” she says. “He grabbed me and we ran away from it and we were both giggling and he said ‘I’m a lover not a fighter,’”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

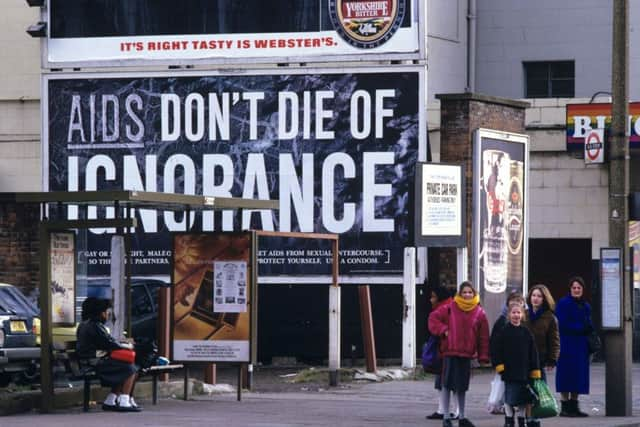

Hide AdBy then most of the young people Gilbertson knew were using heroin. They shared needles stolen from the bins in the Edinburgh City Hospital. They didn’t know about Aids. Not yet.

Then Raymond found out he was HIV positive. He came home and told Gilbertson everyone he’d slept with or taken drugs with had to be tested. He became sick and was admitted to the City Hospital’s Aids ward. “What is an Aids death like? It’s terrifying; medieval,” Gilbertson says. “They wore those full suits like you see in films about Ebola. Raymond was very unwell. He got tumours in his brain, he went blind, he was convulsing.”

Gilbertson was also diagnosed with HIV, but – unlike Raymond – she was lucky. The virus did not progress to Aids. She came off heroin and now runs a charity called Recovering Justice which campaigns for the decriminalisation of drugs and the destigmatisation of users.

Her campaign work is driven by her memories of those dark days. As Raymond lay dying, she grew progressively angry, but Raymond was resigned. “He looked at me kind of confused and he said: ‘But we’re junkies. This is what we deserve,’” Gilbertson says. “So eventually, what society had been telling him, he believed.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdToday, Glasgow is in the grip of the biggest outbreak of HIV in Scotland for 30 years. A rise in the dual injecting of heroin and cocaine (speedballs) and in homelessness is thought to be behind a ten-fold increase, with 100 new cases between 2015 and 2017.

Though everyone now understands the virus is spread by dirty needles many addicts have gone back to sharing. It seems the lessons of the past are being ignored. It doesn’t help that drugs policy is reserved. The Misuse of Drugs Act, 1971, prevents Glasgow City Council from opening a safer consumption room where heroin could be taken under supervision.

The hostility towards a measure which has been proven to work elsewhere in Europe is all too familiar to those who lived through the Edinburgh Aids epidemic. On the documentary, there is footage of the minister responsible for health in Scotland, John MacKay, arguing that the distribution of clean needles would just encourage more young people to consume. By the time doctors persuaded the government to change its approach, hundreds had been infected and dozens had died.

“Edinburgh was the Aids capital of Europe. Scotland is now the drugs death capital of the world,” Gilbertson says. “There’s a lot of fantastic organisations doing a lot of great work. But if we have an outbreak in Glasgow amongst our most vulnerable population then we have forgotten our history; we have forgotten how to look after people; we have forgotten to take community responses; we have forgotten evidence-based policy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad